By Louise Hunt

- Monoculture palm oil production has come at the cost of rainforest habitat, particularly in Malaysia and Indonesia.

- Researchers are conducting experimental trials in Malaysian Borneo to see if native trees can be planted in oil palm plantations without significantly reducing palm oil yields.

- While still in the initial stages, the experiment is so far showing there are no detrimental effects to oil palm growth.

- In fact, interplanting with native forest trees may benefit oil palm, with the researchers finding oil palm trees had more leaf growth in agroforestry plots than in monoculture ones.

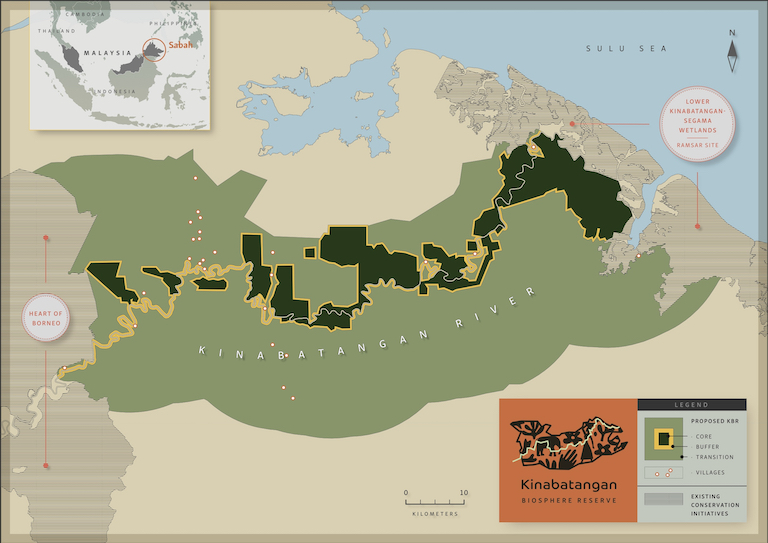

The Kinabatangan River is the last major area in Malaysian Borneo’s Sabah state with a semblance of forest corridor linking the interior rainforest with mangroves on the east coast, according to Marc Ancrenaz, scientific director of Sabah-based NGO Hutan. It’s a hub for biodiversity, with orangutans, proboscis monkeys and pygmy elephants among the threatened species that dwell there.

But most of the floodplain has been converted to agriculture, mainly oil palm, leaving a “very fragmented, very degraded,” landscape, Ancrenaz says.

“We still have about 50,000 hectares [124,000 acres] of protected forest on both sides of the river, but they are isolated from one another, so a lot of wildlife is stuck in these forest islands. Unfortunately, they are not enough to sustain viable populations of orangutan and other species,” says Ancrenaz, who co-founded the community-based environmental NGO with Isabelle Lackman 30 years ago with a mission to conserve Borneo’s iconic wildlife.

Monoculture oil palm plantations expanded rapidly in Malaysia and Indonesia in recent decades. While they’ve been a commercial success, the large-scale deforestation of rainforest and peatlands that they’ve wrought has damaged biodiversity and ecosystems. “We know we need to diversify this landscape. So far, the oil palm industry views other trees as competitors, that’s why they go for monoculture,” Ancrenaz says.

But this mindset is starting to shift, as agroforestry, in which crops and livestock are grown among native trees and shrubs, is gaining traction as a potential solution to regenerating soil health and mitigating climate change impacts, both of which pose challenges to oil palm growers.

With vast areas of plantations in Sabah requiring replanting over the coming decade, there’s a window of opportunity to redesign plantations with agroforestry features that also serve the purpose of slowly knitting the fragmented landscape back together.

This is the aim of TRAILS, a pioneering research project that’s testing how oil palm and native species can grow together from the planting stage. Proponents say this will provide crucial information for innovations in replanting. Hutan (“forest” in Malay) is a partner on this project, which is run by the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD) in collaboration with Putra Malaysia University (UPM).

The project began as an unconventional (for the time) conversation between Ancrenaz and agronomist Alain Rival, regional director at CIRAD.

“Almost 10 years ago, I had this crazy discussion with Marc on ‘why don’t we put the oil palm and the forests together and build an agroforestry project?’ As a vet, Marc understood all the benefits we could get in building wildlife corridors using oil palm and forest species,” Rival says.

Hutan was already working with the Melangking oil palm plantation (MOPP) to reforest a 1-kilometer (0.6-mile) wildlife corridor along a riverside buffer zone. This partnership paved the way for MOPP agreeing to host the agroforestry experiments, which are taking place in a 39-hectare (96-acre) plot within its 8,000-hectare (19,800-acre) estate in Kinabatangan.

The project aims to find agroforestry models that will ultimately reduce fragmentation by reconnecting the isolated patches of forest. This will help biodiversity and help communities by making coexistence between people and wildlife easier, as well as build in local climate resilience, Ancrenaz says.

“The idea is to put in more trees to create a micro-climate that is more humid and less hot. And by increasing the size of natural forest and creating a connected landscape, we think that animals will have less incentive to go in people’s crops so it will be a way to minimize wildlife conflict,” he says.

Rival adds: “We are hoping to show that agroforestry systems are more resilient and more able to absorb the climatic shocks we have in the region.” He points to the 2015 El Niño year, which was “very dry and there was a lot of mortality in the plantations and the forests as well.”

Four years in, with a pause during the COVID-19 pandemic, the project is trialing three different planting designs in adjacent plots: interplanted rows, with oil palms mixed with two different densities of forest trees; mixed tree plantation, with forest saplings from 10 different native species and no oil palms; and tree islands, with patches of native trees among the oil palms.

These experiments are aimed at providing information about the ability of oil palms to grow in concert with native trees, the best combination of tree species, and their compatibility with oil palms.

The project is also pushing the boundaries on traditional models, with one mix doubling the density of forest trees in the interplanted rows.

“We know that it’s too much to have a lot of shade, but we want to push this agroforestry density to its limits with the palm still able to produce fruits and be a good business for the planter,” Rival says. A 30-40% reduction in oil palm yield will be unacceptable, but a 5% compromise on productivity could work if it brings growers other benefits, he suggests, adding: “This balance is really the backbone of the project.”

While it’s still in the initial stages, the experiment is so far showing there are no detrimental effects to oil palm growth, according to Rival.

“The first oil palm fruits are appearing now without any catastrophe on the ground,” he says. “They don’t look late in terms of the fruiting sequence so that’s a good result for the owner. We can expect to have quite a reliable yield in three to four years. We will compare the standard plantation with agroforestry quite easily.”

Ph.D. students Nur Azleen and Wei Yan Yeong at UPM are respectively monitoring nutrient competition — comparing how much nitrogen is taken up by oil palm and native forest trees in the mixed tree plots, which can affect crop yield — and evaluating soil microbial diversity in the different experiments.

“I’m trying to find out if planting more diverse aboveground species will influence more belowground activity, especially microbes, and how that will increase or maintain carbon storage in the soil,” Yeong says.

She says she expects the agroforestry plots to have more microbial communities belowground. “A lot of studies have shown that increased microbial abundance does help with the soil health in the long term, it helps to recycle nutrients more efficiently, it’s definitely better for the environment if we can reduce nutrient leaching due to excessive fertilizer inputs,” she says.

It will likely be a decade before the soil carbon has stabilized enough to produce concrete data, but previous studies have shown that increased soil microbial diversity can potentially increase carbon dioxide storage in the ground, Yeong adds.

Azleen is measuring the difference in oil palm growth between the monoculture plots and the experimental plots. She says that while the palms are not yet mature, those in the agroforestry experiments are already showing a difference in frond growth.

“The agroforestry plots with the two species of forest trees had higher frond numbers compared to the monoculture, and also more than the plot with one forest tree species,” Azleen says.

This correlates with previous research that has found multispecies tree planting can produce better yields than monocultures, “because the amount of organic matter litter that falls onto the ground can be composted and reused by the trees, it also relates to the microbial diversity and richness,” Azleen says.

TRAILS is also experimenting with what happens if the density of oil palms is decreased from 143-163 palms per hectare (58-66 per acre, which is standard practice in Malaysia) down to 100 palms per hectare (40 per acre), increasing spacing from 9 by 9 meters to 12 by 12 m (from 30 by 30 feet to 39 by 39). So far, most industry research has focused on how to increase the density, Rival says. He adds the planters he spoke to said there would not be much difference because with more light interception the palms will compensate by producing more fruits.

“For me, it’s step number one, if we can show there are no clear consequences in decreasing the density, it opens the door for oil palm-based agroforestry for decades, because a lot of clever people in different environments will grow different things in the spaces,” he says.

Even without introducing agroforestry, reducing oil palm density has the benefit of reducing the amounts of chemical inputs needed, as “more trees require more fertilizer,” Azleen adds. “If you abuse the soil by planting the maximum amounts of trees, it causes the soil to reduce its fertility even quicker, rather than planting a sparse distance of trees.”

The experiments are taking place within the standard management of MOPP’s estate, following the plantation’s normal operating schedule of fertilizing and harvesting. “We didn’t want to change the system, we just want it to be a reflection of what is really happening in a plantation when we change from a monoculture estate to agroforestry estate,” Rival says.

However, if the agroforestry trials do lead to improved soil quality, then it could be possible to reduce the use of polluting chemical inputs, according to Ancrenaz.

“We want to show with this agroforestry experiment that if you mix [native] trees with palms, you actually maintain your yield at the same time you minimize chemical inputs, so you save money in the end,” he says. He adds that this would be particularly helpful to smallholders, whose biggest expense is fertilizer.

While the TRAILS project will be collecting data over the next couple of years, there’s already a growing body of evidence on the positive environmental impacts of introducing agroforestry strategies in oil palm. For instance, the IUCN Netherlands has recently published a visual guide for boosting biodiversity in oil palm plantations by using agroforestry techniques.

One of the most influential studies for the TRAILS project was the EFForTS (Ecological and Socioeconomic Functions of Tropical Lowland Rainforest Transformation Systems) trial conducted by the University of Göttingen, Germany, and based in Sumatra, Indonesia. The study concluded that planting native tree species in clusters between mature oil palms to create tree islands of agroforestry increased biodiversity and ecosystem functions without reducing yields, according to a paper published in the journal Nature in 2023.

The two research teams have visited each other’s projects and EFForTS contributed scientific advice to TRAILS on planting design.

“We learned a lot from the EFForTS trial, the fact that within a couple of years you can see an effect on biodiversity by just mixing trees was really a key paper and motivated me even more,” Rival says.

The TRAILS project takes this research forward by testing agroforestry from the planting stage, which will help researchers evaluate the long-term process, according to Clara Zemp, who was scientific coordinator on the EFForTS trial from 2016-2021 and is now a professor at the University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

“It is a very interesting and complementary project to the agroforestry research in oil palm that already exists, especially in Sumatra,” Zemp says.

She suggests the multidisciplinary nature of the TRAILS project, which involved industry from the start of the project, could mean the agroforestry designs are more directly relevant for oil palm growers, “so potentially, it has more possibilities for direct implementation,” she says.

Asked if she thinks there’s a readiness among the wider industry to move away from monoculture to introducing agroforestry systems, Zemp says she’s “quite convinced that eventually this will happen at large scale because the industry is under multiple pressures. It’s a question of what will be the incentives to do so relatively soon.”

Rival agrees: “We hope that [TRAILS research] will convince more people, especially the young planters, that we have to change the way we’re planting oil palm,” he says. “I know that it’s going to take time, but we need champions, like MOPP, that are a bit more open to risk.”

A proposal to create the Kinabatangan Biosphere Reserve (KBR) under the UNESCO Man and Biosphere Program could help TRAILS in its aims by sowing the results of local experiments in the wider region. The proposal has been developed by Sabah Biodiversity Centre (SaBC), the government agency that oversees conservation in the state. Covering 413,866 hectares (1.02 million acres), it would enable the reconnection of an ecological corridor linking the Heart of Borneo conservation zone with the Lower Kinabatangan Segama Wetlands Ramsar site — designated as a wetland of international importance — in the extreme east.

The TRAILS project will be under the KBR management plan if it gets the go-ahead; a decision is expected in the coming months, says Ken Kartina Khamis, SaBC director.

“The KBR provides a structured framework to harmonize the biodiversity and also the local communities through one common leadership, so people and nature co-exist along the corridor. The government, the local businesses and communities will come together to restore the ecological integrity of the Kinabatangan,” she says.

“For us, we see the opportunity that if the KBR is created, the people that are inside the KBR would have to manage plantations in a more sustainable way, so this could be leverage for us to replicate what we do at TRAILS,” Ancrenaz says.

“What we want to see is more trees, whether it’s forest corridors or agroforestry, as long as it’s more trees in the landscape,” he says.

Follow our Facebook page ConserveByU for our latest updates.